Excerpt from The Sun Times, Owen Sound, article #942575,

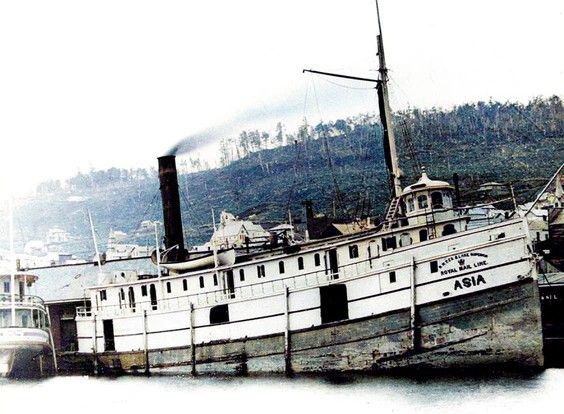

At one o’clock in the morning on Sept. 14, 1882, the wooden steamer Asia left her berth in the darkness of Owen Sound’s harbour. The Asia was on her way to a rendezvous with a storm. It would be the nine-year old ship’s last voyage and the beginning of a Great Lakes legend.

The Asia was bound for Killarney, Manitoulin Island, North Channel ports, and Sault Ste. Marie. As he put the lights of Owen Sound behind her, Captain John Savage logged his concern over a rising wind from the southeast and the first of the choppy waves that promised an angry lake, dead ahead.

The Asia made one stop at Presqu’isle for fuel wood. There, Captain Savage deliberated on the wisdom of continuing in the face of an oncoming storm. But he was a company career officer and there was cargo and passengers to deliver. His concern would grow over the next five hours as the Asia bucked inceasing winds, making her way up the Bruce Peninsula.

At seven in the morning, Captain Savage turned the Asia east toward the lumber port of French River just as the full fury of the equinoctial gale broke from the west. The Asia was suddenly in extreme danger. Dunk Tinkis told of that moment. My uncle was awakened by the rolling of the ship and springing out shouted to me, “Dunk, jump up, the boat is doomed.” The expression on his face was alone sufficient to convince me that it was only too true and throwing on my coat we both rushed on deck. The sight that met my eyes was a fearful one. The storm was raging, the wind blowing a perfect hurricane and the waves appeared to be rolling mountain high.

The scene on the deck of the Asia was chaos. Many passengers were too ill from the tremendous pitch of the ship to reach the rails. Others fought for the few life preservers available. Tinkis tells it best. “Until my dying day, I shall never forget the cries and shrieks, a majority being on their knees, crying for mercy and deliverance, and all realizing that they were face to face with death.” Death would come to all but two.

Captain Savage made one last attempt to save the Asia and her human cargo, turning to run for Lonely Island, dimly seen ahead through a flying screen of lake water raised by 90-mile winds. The Asia never made Lonely Island, careening over on her side, stern foremost, swallowed by an angry sea. The unthinkable had happened. A fully loaded lakes steamer had turned turtle in the midst of a giant storm. Even today, the total loss of life is unknown. It has been estimated that 24 crew members, 85 male passengers, 11 women and 9 children were lost that day. That being 129 and in other records, the total is put at 125.

A single lifeboat remained adrift among the floating bodies and debris. Dunk Tinkis was an eyewitness to the tragic deaths that came in the minutes following the disappearance of the Asia. “I looked towards the wreck, where nothing was to be seen but a struggling mass of humanity, who were clinging to pieces of timber and other wreckage to prolong their lives even for a few seconds. I saw a boat but it filled with water and sank.” Tinkis managed to find a metal lifeboat with watertight compartments. When the 17-year old deckhand reached the small craft it was already packed. Thinking it was his last hope, he called to the purser, John McDougall, to give him a hand. McDougall shouted through the storm, “Oh, I don’t think it of any use.”

Christy Ann Morrison was 18 years old and a resident on the Blind Line near Bognor in Sydenham Township. She too was a survivor. Christy Ann leapt from the deck of the sinking Asia and was pulled into the lifeboat by her cousin, First Mate John McDonald. Another relative, Second Mate Archie McNabb, also huddled in the frail shell.

Dunk and Christy Ann were strong and young. The waves were like mountains and during the next few hours, the teenagers would be called upon to make every effort to stay alive. Five times the lifeboat was turned over, spilling the shipwrecked and nearly frozen passengers into the boiling water. Each time, Tinkis and Morrison were able to hang on to the ends of the overturned lifeboat waiting out waves, crawling back into the swamped craft. After each dumping, there were fewer to take up precious space. And then there were only seven.

With the lifeboat some 20 miles from any land, there was only one oar to propel and guide the craft. Still, the water began to calm, the waves diminished and the lifeboat settled more easily in the troughs. And still they died, slowly, one by one: exhausted, hypothermic, energy drained, their spirits destroyed.

Christy Ann Morrison testified at the inquest that, “The men all died quietly. They seemed to go to sleep. The mate put his head up to my face in the dark, and asked if it was me. I said ‘Yes.’ My hair was flying around and he seized it in his death grip and pulled my head down. I asked the captain who was near, to release my hair. He did so, and the mate soon breathed his last.”

And then land was sighted at five in the evening. As the cry of “saved” was sounded, the surviving lifeboat passengers sang, “Pull for the Shore” and “The Sweet By-and-By.” But still they died. Mate followed mate. McDonald and McNabb. Christy Ann Morrison comforted her relatives. Tinkis remembered. “The poor mate was supported by the brave, heroic girl, who can truly be called the Grace Darling of modern times.”

Captain John N. Savage was the last to die, just as the Byng Inlet lighthouse came into view. He seemed to fall asleep. The teenagers tried to wake him. He answered, “Yes,” saying he would be up in a moment. The moment passed and he was dead.

The lifeboat struck the beach at dawn. Aboard it were five dead and two young, exhausted survivors. Tinkis was able to remove the bodies from the craft as the pair staggered ashore. The day passed on the lonely beach as they slept in their sodden clothes, huddled together. The next morning brought relief with a passing Ojibwa in a canoe who gave them food and took them to Parry Sound.

The news of the catastrophe spread through communities around Georgian Bay. There was wild excitement when Dunk and Christy Ann reached Parry Sound. Surely, there were other survivors on some isolated island or beach? The search went on for weeks as hope died slowly. Bodies were found, singly and in pairs, arms locked around each other, many miles from the grave of the Asia.

Chisty Ann Morrison married Albert Fleming, had a son, living a quiet life in Kilsyth until her death in 1937 at the age of 74. Douglas “Dunk” Tinkis ran a general store at Manitouwaning before managing a hotel in Little Current. His was an early death at the age of 36 from accute rheumatism. 1882 was additionally cruel to John Savage’s wife who not only lost her husband but her son. He drowned while skating on ice that had been worked by ice cutters. And Mrs. Savage was also suffering from typhoid.

The wreck of the Asia was a national story, one that prompted the government into a resurvey of the waters of Lake Huron and Georgian Bay led by John G. Boutlon, a hydrographer from the Royal Navy. The sinking of the Asia passed into history, marked by many retellings in both prose and poetry.

Printed anonymously in a local newspaper, and sung for years there-after by sailing crews:

Loud raged the dreadful tumult,

And stormy was the day,

When the Asia left the harbour,

To cross the Georgian Bay.

One hundred souls she had on board,

Likewise a costly store;

But on this trip, this gallant ship

Did sink to rise no more.

With three and thirty shanty men

So handsome, stout and brave,

Were bound for Collin’s Inlet

But found a watery grave.

It was an awesome tragedy, a grim reminder of the power of destruction that can be Georgian Bay when the gales of autumn rise again.

Christie Ann Morrison’s brother Murdock Morrison was married to Kate Murray, sister to Kenny Murray, father of Helene Murray Scott who is responsible for recording the majority of the history of Stokes Bay and writing the book Old Timers’ Tales.