A collection of media and stories related to The Big Seige in Stokes Bay of 1952, including first hand accounts and newspaper articles.

Table of Contents

The Big Seiche by Vincent Elliott

May 5, 1952

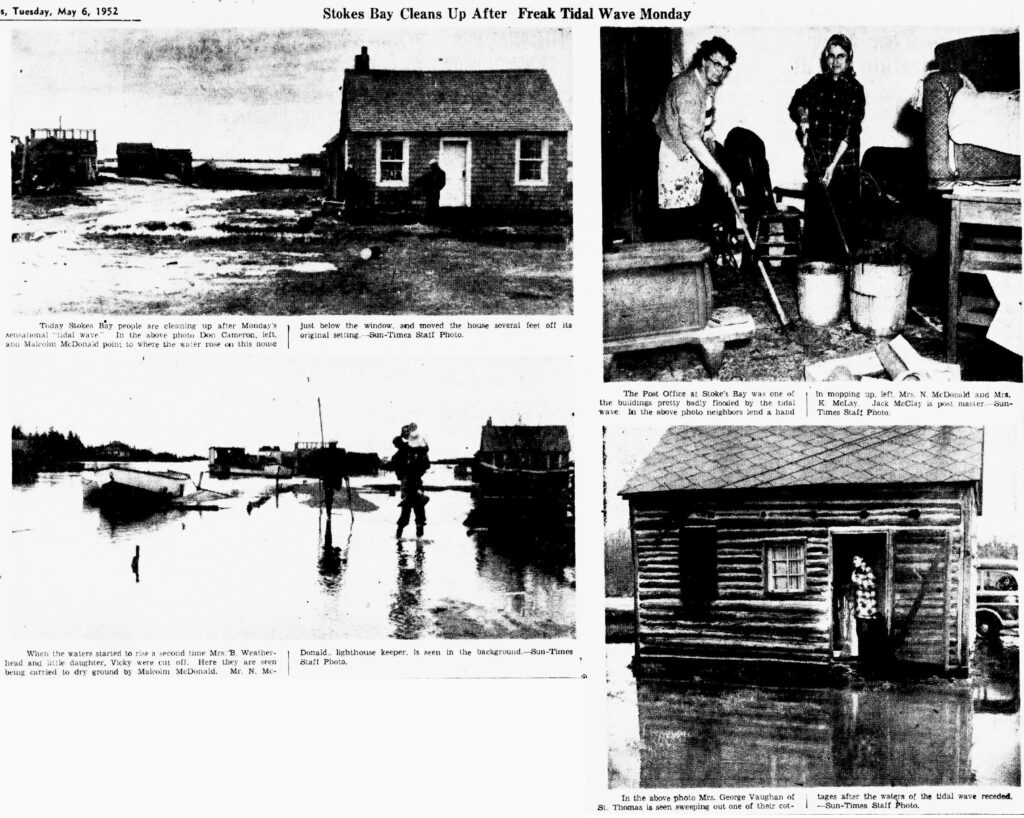

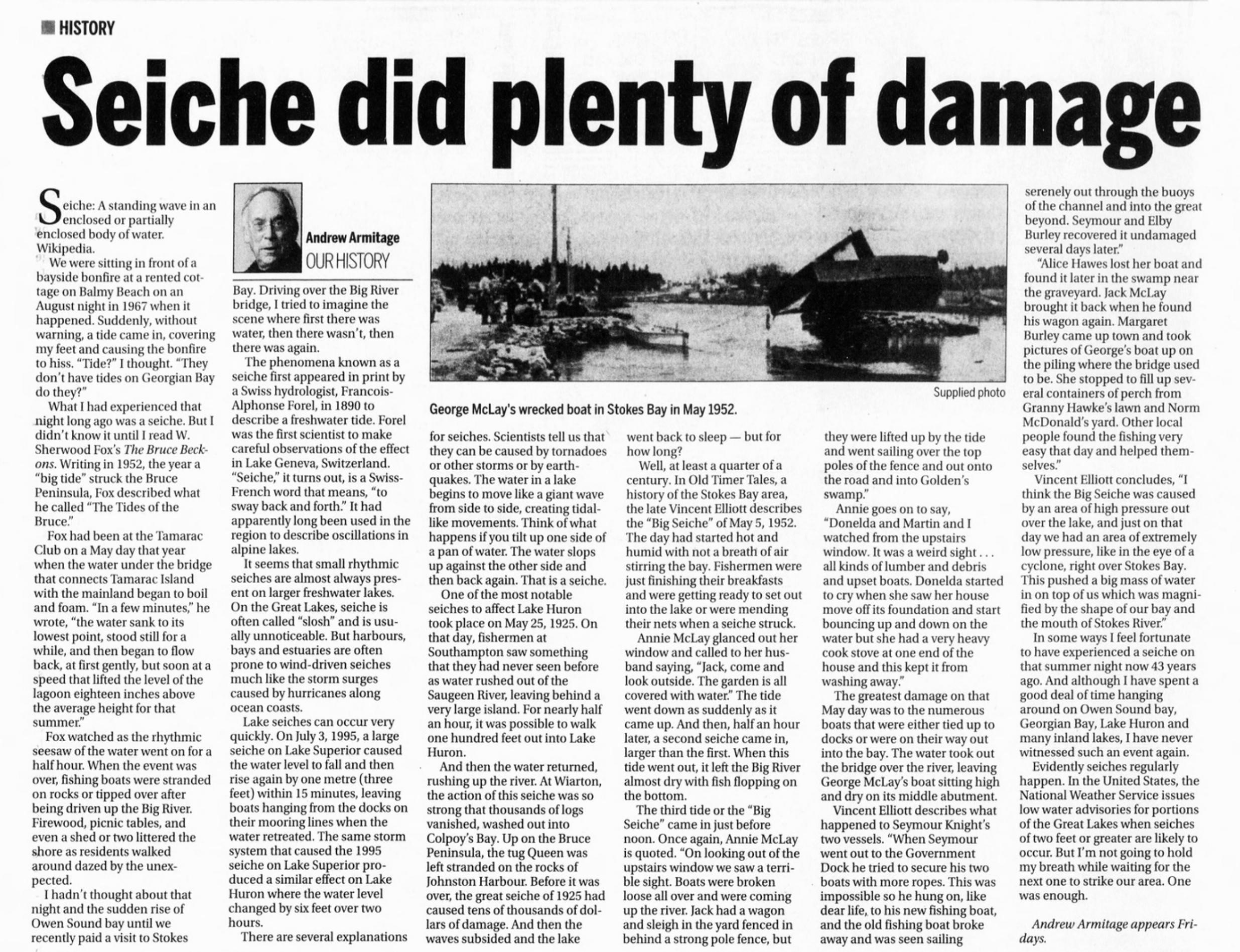

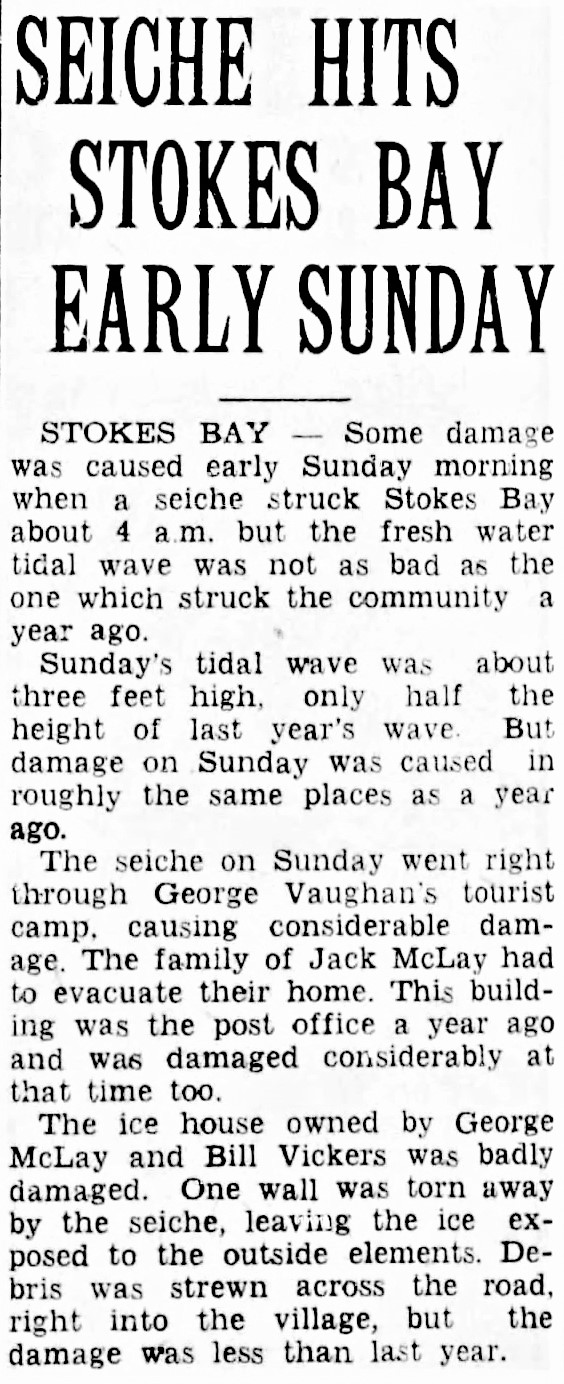

The Big Seiche of 1952 in Stokes Bay will be long remembered by the people who had to clean up the mess, or who lost cabins, furniture, boats or wood, but since no one was hurt, today it is just an amusing story from the past.

It all started with what looked like a hot, humid day. Not a breath of air stirred the gently flowing Stokes River and a faint mist lay over the Bay. The fishermen had just finished their breakfasts and were getting ready to start the day fishing or mending their nets or getting the boats ready for the coming fishing season. George McLay had his boat drawn up on the shore for last-minute repairs. Seymour Knight had a brand-new boat tied up at the Government Dock and his old boat tied up beside it. Malcolm McDonald had his lighthouse boat tied up to a piling of the bridge and a fencepost on Jack McLay’s lawn. Kenny McLay left his boat at Howdenvale, and the other Stokes Bay boats were tied up loosely along the river front. My own little aluminum boat was tied up beside Garny Hawke’s despite the fact that Garny had wiped out my last wooden boat by throwing an anchor through its bottom in the dark one night.

At 6:00 a.m. Annie McLay glanced out the window and called out to her husband, “Jack, come and look outside. The garden is all covered with water.” The water had come up level with the riverbank and was now gently flowing across the road. This is the first seiche to arrive. There were to be three that forenoon, each getting more violent. In this article I will simply call the rise in water a “tide” for want of a better word. This tide soon went down but the village people were now aware that something was happening. At this time, I came down to the shore to go fishing with Ralph Beacroft from Wallaceburg. I stopped to take a picture with the water up around my knees but by the time I had things in focus I was standing on dry land again. In the lull after the first tide, we took off into Stokes Bay, so were not to see the things that were shortly to happen in the village.

About half an hour later the second tide came in. This was bigger than the first and covered the road for some distance up town. People became alarmed about the safety of their boats and put extra ropes on them. This tide went out with a rush, leaving the river almost dry and fish flopping on the bottom. Kenny McLay said, “I could have walked across to Garden Island in my rubber boots.” As the second tide rushed out, Malcolm McDonald, to save the lighthouse boat, jumped into it, cut all the ropes, and rode it down the river. He checked in with his parents manning the light as Knife Island, but they had not noted any disturbance so far in that part of Stokes Bay. This second violent tide should have warned the local people to be ready for anything, but no one suspected that the worst was yet to come.

The third tide, or Big Seiche, came in just before noon. Here are the exact words of Annie McLay who ran the Post Office beside the bridge:

“I awoke about 6:30 at my usual time to get up. I was Postmistress and had to have the office open at eight o’clock. Martin was going to High School in Lion’s Head then and had to leave to catch the bus. On looking out the bedroom window I saw the water up on the road and some on the garden. I called on Jack and Martin to come and see this unusual sight. The tide receded and in a few minutes the river was dry. I got breakfast and was just going to sit down when we saw the water running up the river again. Malcolm’s boat was tied up at the bridge and Jack went out to put another line on it. He tied this line to our fencepost. Earl McArthur and Donelda were living in a cottage beside us, and when they saw the water coming in Donelda came to our place. There was no wind at all, but a distant rumble of thunder. When the water started coming in under the door, I picked up the mailbags and everything belonging to the Post Office and put it up high. Martin and Donelda picked up a few things and got one chair up on the table. By this time the water was getting so deep we took the cash box and money from the Post Office and went upstairs.

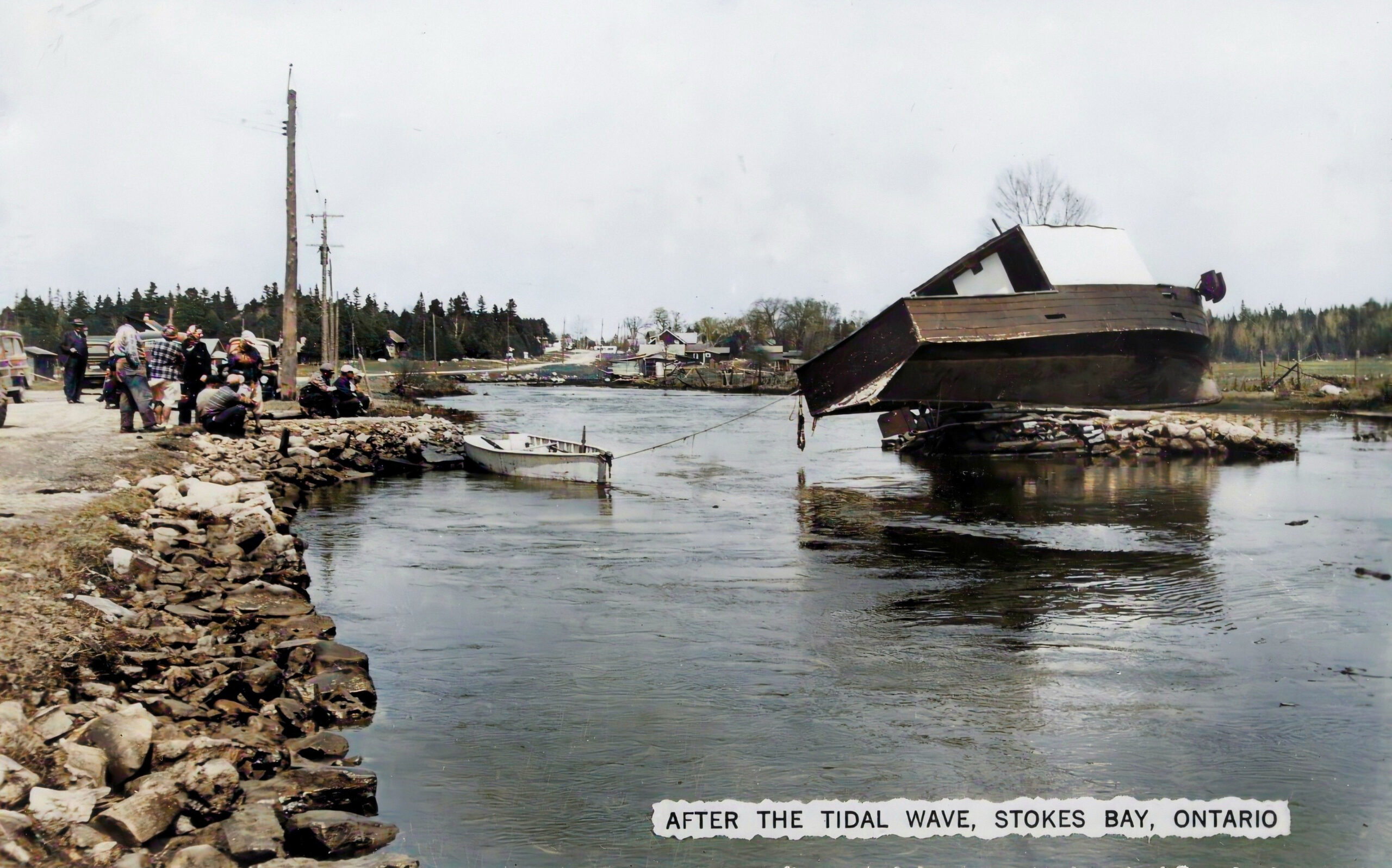

“On looking out of the upstairs window we saw a terrible sight. Boats had broken loose all over and were coming up the river. George McLay’s boat had come off the shore and was coming up the river faster than a motor could have driven it. Jack went out to save some boats, but he couldn’t get home against the tide rushing in so fast, and had to go up the road towards the store. George Vaughan, from his fishing camp, put his wife Alice on his back and carried her ap the road, stopping to rest on the front steps of McLay’s Store. Jack had 7 cords of wood and 50 fence posts stacked in the yard and Earl McArthur had another 7 cords of wood piled beside his cabin. All this was washed away and never seen again. Jack had a wagon and a sleigh in the yard fenced in behind a strong pole fence, but they were lifted up by the tide and went sailing over the top poles of the fence and out onto the road and into Golden’s swamp.

“Donelda and Martin and I watched from the upstairs window. It was a weird sight… all kinds of lumber and debris and upset boats. Donelda started to cry when she saw her house move off its foundation and start bouncing up and down on the water, but she had a very heavy cook stove at one end of the house, and this kept it from washing away. The water took out the bridge and left George McLay’s boat sitting high and dry on the middle abutment. “When Allan McLay came in from Tamarack he saw the water rushing in and called to Roddy Smith to get out of his house and up the road. Roddy couldn’t move and said he was all right, but as he saw the water getting deeper in his house it wasn’t long before he was glad to get out. As Roddy was going out the front door a muskrat came swimming in the back door.”

In Annie’s account she doesn’t mention the second tide. I checked the impossible “Muskrat” story, and it is true! There were a lot of other incidents connected with the Big Seiche. Here are some of them:

When Seymour Knight went out to the Government Dock he tried to secure his two boats with more ropes. This was impossible, so he hung on, like dear life, to his new fishing boat, and the old fishing boat broke away and was seen sailing serenely out through the buoys of the channel and into the great beyond. Seymour and LB Burley recovered it undamaged several days later.

A tourist at Look About Bay got up and reached down to get his shoes. He put his arm into the water, and then found his shoes floating under the bed.

The owners of McLay’s store near the bridge awoke to see a large box of crackers floating past their bed.

A tourist at the Government Dock claimed that all wood washed up on the shore was “Driftwood” and belonged to the finder. Despite the fact that he knew whose wood it was, (mostly Jack McLay’s and Earl McArthur’s) he proceeded to gather it up and add it to his own woodpiles.

When Annie McLay was upstairs watching the tides, she heard a bump and found her chesterfield floating around her living room. A few minutes later she heard an even bigger bump and found that the tin heater had risen up and was behaving like a boat while the stovepipes came crashing down, getting soot all over the room and through her cupboards.

Margaret Burley came uptown and took pictures of George’s boat up on the piling where the bridge used to be. She stopped to fill up several containers of perch from Garny Hawke’s lawn and Norm McDonald’s yard. Other local people found the fishing very easy that day and helped themselves.

Alice Hawes lost her boat and found it later in the swamp near the graveyard. Jack McLay brought it back when he found his wagon again.

George Vaughan’s cabin was washed right away and landed across the road in the swamp.

Annie McLay’s cat kept bringing in drowned kittens all morning and putting them on her front doorstep.

Lobsinger came in from the lake and said, “Where is my dock?”

Jack said, “Just tie your boat to my fence post.”

Between tides that morning Ralph and I had gone out into the bay fishing. What happened to us was just as weird as Roddy’s muskrat or George’s boat. We tried to fish in the “deep hole” off McDonough’s, but a dense fog came in and we couldn’t see even a few feet away. We had to stop fishing because our lines seemed to take off violently in one direction for no apparent reason. At this time, we must have been rushing along at a fast rate, but because of the fog and the movement of the entire surface of the water we had no sensation of going anywhere. After about an hour the fog lifted, and we found that we were not in Stokes Bay at all but had crossed a spit of land and were now in Gallie’s Bay!

How can a seiche cause a flood like the one on May 5, 1952? I don’t think it can.

A seiche is really a transverse vibration of the water in the lake. If you tilt up one side of a washbasin, the water slops up against the other side and then back again. That is a seiche. There are longitudinal seiches making quite strong currents in Lake Huron in a North-South direction. The commercial fishermen encounter these. The seiches the sports fishermen know most about are little crosswise tides that come in and go out about every twenty minutes. These raise the water only a few inches to a foot and are noticed especially before a storm. We are very aware of these because the fish bite best just when the “tide” changes. At the “Reversing creek” at the foot of Dorcas Bay you can see this periodic inflow and outflow of water. Stokes Bay is also funnel-shaped, and this intensifies the effort of a seiche. In Stokes Bay “tides” may come and go every ten minutes because the vibration may be reflected by the shore of Lyall Island and cause a vibration with a vibration.

Another thing that could cause a “tide” would be a strong wind. In Florida I’ve seen all the water blown out of the shallow mangrove swamps into the ocean so we couldn’t fish for three days. A strong west wind would magnify the effect of a seiche, but there was NO wind on May 5, 1952.

I think the Big Seiche was caused by an area of high pressure out over the lake, and just on t at day we had an area of extremely low pressure, like in the eye of a cyclone, right over Stokes Bay. This pushed a big mass or water in on top of us which was magnified by the shape of our Bay and the mouth of Stokes River.

Twenty-nine years have passed since the Big Seiche. The older people have almost forgotten it and the young people don’t know about it or hear such stories with disbelief. Yet tourists are still building cabins along the mouth of Stokes River, and these people are blissfully unaware that there is no reason in the world why this couldn’t happen again. We could have another “Big Seiche”.

By Vincent Elliott – 1913-1988.

An Excerpt From “The Bruce Beckons” by Dr. W. Sherwood Fox

“The setting of the stirring action I am now about to describe is Tamarac Island in Stokes Bay, site of the Tamarac Club. The island is a narrow ridge of limestone rising thirty feet above the surrounding water and has a length of half a mile. An excellent example of the carving power of ice, it lies with itslong axis pointing straight into the southwest along the path of the glaciers themselves. On its western side and parallel to its extends a shallow glacial trough which at its south end broadens out into a spacious beaver meadow. Trough and meadow together hold enough water to form a large lagoon which, were it not for the regular churning of the “tide,” would be hopelessly stagnant. Not far from the north end of the island the channel that divides it from the mainland contracts to the neck of water about fifty feet wide. Here, back in the eighties, lumbermen threw across the little strait two long, stout pine trunks as stringers to carry the planked floor of a bridge strong enough to bear the weight of the most heavily laden wagons. In the process of providing each end of the structure with an abuntment of rough stone the builders narrowed the passage to twenty feet. This had the unforeseen effect of amplifying several times the force of the seiche as it rushed back and forth between the lagoon and the bay. Since the channel at this neck is a least ten feet deep the volume of water passing through it is very great and is as sensitive to the slightest variations of pressure as is a thermostat to fine changes in temperture. Its quickness to register them is clear to any one who looks into the water from the bridge. Nowhere else in the Great Lakes have I ever found a spot where one can view so convincingly the reality, the constancy, and the irresistible power of the secondary seiche of a freshwater sea.

Now our scutiny of this eternal flux and reflux is more than an academic pastime. It is of practical import to angler and navigator. Long has the little strait by Tamarac Island been famous in this region as a gathering place of the black bass. The constant agitation o fthe current charges the water with oxygen and the fish throng there for a breathing spree. The stories of fabulous catches made in the narrows by loggers and swyers of the threescore years ago are not just reports of actual fact magnified by the memories of what might have been. For that, I have the word of one who, in later life a bishop, was in those early days a member of the timber gangs who cast their angles from the bridge when the day’s work was over. In his late teens he was in the employ of his father, a master lumberman, on Tamarac Island. Many a leisure evening did the young man pleasantly spend in whipping the reversing waters. At times so richly were his efforts rewarded that the good bishop still fears to cite the true figures lest he be regarded as just an ordinary fisherman – just one of the common guild who suffer from chronic inflation of the faculty of calculation. Not a word more would he say than this – with a convincing smile: “The rosiest of the tales of fishing here in the old days are all true.” He smiled again when I told him that even in these lean days of angling the bass still congregate by the bridge.

The day of the Great Tide! And many there are who remember it. Two aspects of it stand out in their memory above all others: their amazement that a scene of such violence as one usually associates with a tempestuous ocean could take place on an inland lake; their fears at the thought of the stupendous damage that this strange phenomenon, suddenly bursting from the blue, might produce. The exact year I cannot recall: it seems to have been about fifteen years ago. This at least is clear: it happened in one of those few summers when the reef in mid-channel between Tamarac and Garden Islands projected above the surface like a sharp-peaked cairn. So distinct was it that it was its own danger sign to warn strange navigators to give it a wide berth.

Dawn that day in mid-July brught with it an unwonted lnguor that became perceptibly heavier as the hours shuffled on. Its weight pressed down upon man and beast alike. The clumen’s inveterate passion for going a-fishing yielded to a leaden listlessness: no hampers were packed that morning for shore-dinners at Pleasant Harbour or Little Pine. Even the lonely club cow and a neighbour’s horses grazing by the lagoon and the beaver meadow showed no zest for the lush marsh grasses. Perhaps the peculiar atmosphere drugged our fancy into working overtime, but at the time it really did see that there was less snap in the hop of the grasshoppers and in the leap of the frogs in the grassy fringes of the lagoon. The barn swallows as they swooped and darted and dodged over the water did not seem so sure of themselves as they usually were, and the gulls, which generally spent their mornings cruising over the bay, seemed chained in a long line to the peaked roof-ridge of the old mill.

The water in the channel at the bridge was out of tune with the prevailing mood. The “tide” was busy shuttling back and forth with more than ordinary vigour: the timing between ebb and flow was that common to most days in summer, but each successive pulsation bore with it a greater volume of water. Moreover, whether flowing in or flowing out the stream was ushing with greater speed and vehemence and was making itself heard in a crescendo of splashing and gurgling like a mountaing burn in spate. The normally docile minor seiche we saw in Pleasant Harbour had become here at Tamarac a turbulent reversing river. But in contrast to this agitation of waters we were sharply aware that the stifling air and the broad expanse of Stokes Bay were still as death. A feeling of apprehension almost made us shiver. Everything around us, animate and inanimate, seemed to share it with us. It was manifest that in the vast cauldron of the elements some extraordinary brew was being mixed.

We were not left long to ur guessing. Over the air came a voice giving out a loud, curt warning to mariners. I recall its substance though not its words. “Storm signals out for eastern Superior and northern Huron. All ships of deep draft in lower St. Mary’s River anchor at once. Pleasure craft make for shelter without delay. Expect northwest winds sixty miles followed by torrential rain. Clearing later. Tomorrow clear and cooler.”

Now we knew what brew of weather to look for. Nor was there much delay in the serving of it. The blanket of light grey which from noon onward had been almost stealthily drawn ove the sky had by this time become stained with vast patches of an intensely dark grey. For several minutes it retained this shade and this formation, and then, as by an unseen hand, the fabric was rent apart into long parallel strips between which shone rays of weird, coppery half-light dyed as with diluted blue-black ink. Far to the west we could faintly hear what might be the beating of surf on reefs or on shore, or even the sustained lashing of the tops of many trees. Even as we listened the air began to move slightly toward the southeast; its gentle fanning was welcome indeed.

During this interval of wondering and waiting we became aware that the little strait a the bridge was beginning to boil and foam in an unusual manner. Each incoming seiche was rising higher and with more commotion than the one before, and each ebb sank lower and more noisily than the ebb that had just preceded it. The span between high water and low water was now at least a foot and was increasing with each reversal of the current, which had now the volume of a stream after a thaw. Though we were standing on the summit of the island two hundred yards from the turmoil the roar of it tingled in our ears. The whole scene touched every nerve within us. Even the birds were behaving oddly. In the eerie twilight, like that of an eclipse of the sun I once saw at Rondeau on Lake Erie, the swallows ceased their skimming over the bay and retired to the rafters of the old mill as if for the night. In separate flocks the gulls and the crows set out, each flock in its own direction, with the singleness of purpose that marks a homeward flight. The only living thing within our ken that remained unmoved was a lone great blue heron. Ther he stood like a tall grey stick lodged in the muddy bottom of the lagoon. He had the air of waiting for something worth waiting for. He was right. Doubtless having lived all his summers in this region of inlets he had known such a scene before.

At last, as though bursting through the rents in sombre pall above, a temest tore upon us. The release of all the winds of heaven in one moment from Aeolus’ bag could not have struck with greater violence. The winds we had been hearing in the offing now seemed to take on visible substance. Yielding to their thrust the forest bowed as one tree and stayed thus fixed for many moments. Unable to stand longer before the blast we fled to the shelter of the old mill. Was this a tornado? Surely not in this corner of the globe! Our anxiety was not allyed by the casual remark of a villager born and reared in Stokes Bay: “Well, in July – 1892, I think it was – a twister blowed nearly all Wiarton down”!

No sooner had we dashed into the mill by the front door than we were summoned to the back door by the roaring of the water at the narrows. From the high landing outside we could see the whole lagoon and the bridge. The lagoon was as empty as a drained bath tub! The seiche driving in the same direction as the wind had drawn off all the water whose last dregs, churned into mud and strewn with a litter of dead herbage and brush, were pouring madly through the channel under the bridge. On the bare oozy bed of the lagoon stood out some unfamiliar objects – two wooden logging cribs weighted down with a filling of stones; in the lumbering days long past these had served as end-anchors to booms of logs. Round about them flopped helplessly a dozen or more huge carp and a host of small fry such as perch, sunfish, rock bass, and large shiners. And on these the heron, standing drunkenly a-totter in the gale, was lustily banqueting. As each fish descended to its gastric doom we could plainly follow its progress by watching the lump that passed down the long serpentine neck. It’s an ill wind indeed that blows nobody good!

But the enterprising bird was not left long to his feasting. In a few minutes the water sank to its lowest point, stood still a while, and then began to flow back, at first gently, but soon at a speed that lifted the level of the lagoon eighteen inches above the average height for that summer. And thus the protentous ebb and flow went on for another quarter hour, a rhythmic seesaw of waters on an immense scale. What was the stupendous force that endowed on of Nature’s most placid aspects with a capacity for violence?

For an answer hark back to the warning from the air. This force was as it were a fortuitous conspiracy of barometer, wind, and seiche to work in unison – a pooling of their powers. The light pressure in the east allowed the waters to rise appreciably along the deeply indented shore of The Bruce. The high pressure on the Michigan side weighed down the level there and by the same actin propelled the water eastward. This doubled push, reinfoced by the drive of a near-hurricane, threw up a veritable flood upon the Bruce coast. But this is not yet the sum total of the elemental forces at work here: one has still to reckon with a “tide,” the secondary seiche, a normally unimpressive little movement but nevertheless a dynamic one which is in action night and day, in sunshine and under cloud, in summer and in winter, forever swinging to and fro in accord with the beating of some cosmic metronome. No skill of man can wholly calm it or nullify its hidden power. When Nature happens to be in the mood to add this force to that of the other conjoint elements, she holds in her hand an engine whose possibilities of destruction defy computation.

From all this tumult on the mainland side of Tamarac Island man was entirely absent except as a helpless onlooker. But on the Stokes Bay side it was different. Heeding the warning from the air, lesser water craft of every pattern, from punts with humming outboard motors to sixty-foot luxurious gas-cruisers, were speeding from the open lake in a long broken column to find shelter or mooring at the government dock near the village of Stokes Bay. Most of the vessels wre manifestly unfamiliar with these waters. On they hastened toward the dangerous shoal in mid-channel, innocents abroad in strange waters, unaware of the risk they were courting. The heap of jagged rocks was completely buried beneath a flood tide. By sheer luck most of the skippers safely passed by to one side or the other. But to the dismay of our watching group the finest and largest cruiser of the column was headed straight for the hidden peril. We were helpless to aid: the rush of the wind drowned our voices even shouting in concert, and the untimely twilight and the shifting curtain of spray concealed all signals. Now we knew why “it boots not to resist both wind and tide.” Before our anxious gaze the graceful craft rode straight on to the lurking shoal. Her bow rose abruptly and her stern dropped. In that position she came to a sharp stop and stood as though impaled on an unseen spike.

But we were not the sole witnesses of this scene. From the government dock a rowboat struck out for the stranded cruiser. Even as the oarsmen sped toward her a strong ebb of the seiche set in and the water began to subside. By the time the rowboat reached its goal the peak of the shoal was standing a foot above the water. Upon it was perched the handsome vessel like a streamlined Noah’s Ark come to rest on the summit of a miniature Ararat.

But while the two crews conferred the dark blanket of cloud overhead was ripped again and again by jagged strokes of lightening. In a moment large solitary blobs of rain began driving through the air at a rakish slant. After that came the deluge. How long the cataract decended I cannot recall; it seemed to promise no end. In its falling it quickly beat down to a dead level the foaming crests of the breaking swells and ironed out the wrinkles of the wavelets. By the time the clouds had vented themselves of their burden the rain seemed to have subdued even the fury of the gale to the pace of a normal midsummer afternoon breeze.

Not till then could the true plight of the cruiser be observed. By the veriest food fortune, it turned out, she had slid on an even keel upon the only smooth flat slab of dolomite in the whole reef. Had she veered a hand’s breadth from her course her hull would have been slit open on the points of limestone that bristled all about. A few hours later the lovely craft was gently eased off the detaining rock into the water, unscathed though not unmarred.

While the cruiser was being set free, the sun, now nigh to setting, was beginnig to stain the sky over Lake Huron; the dry cool northwest breeze of evening was already calming nerves that had been taut and touchy all day long; the swallows were dipping and curvetting as usual over the lagoon; the nighthawks were swooping and screeching overhead, and the minor seiche, having spent all her reserves of power in the violent orgy of the daylight hours, was once more in her wonted mood guilelessly and quietly swinging back and forth, back and forth, in the narrows by the old log bridge.”

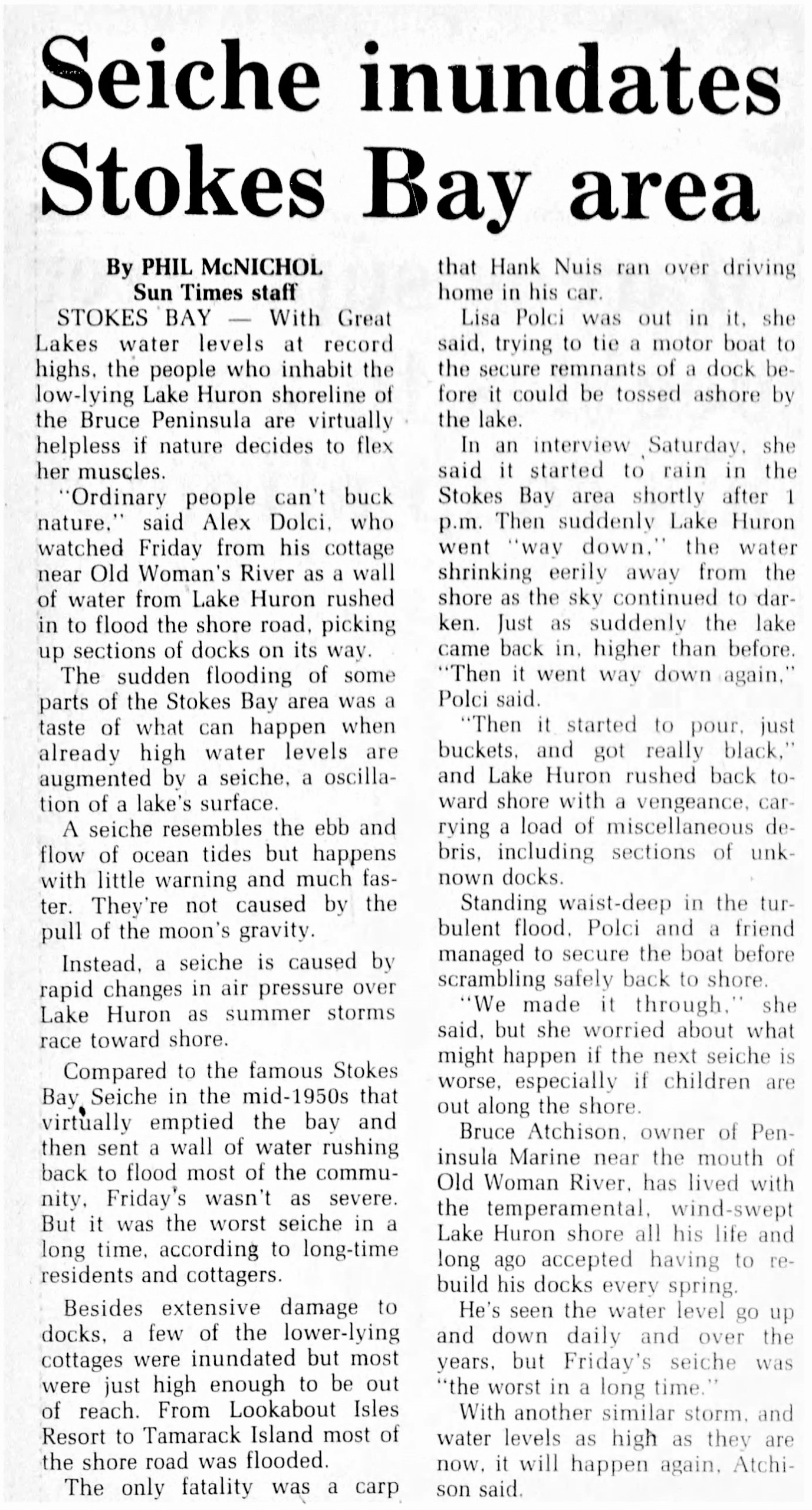

Newspaper Articles

View the newpaper article at a larger size by clicking the picture once to open, then “double click” again to enlarge. Close by clicking the black area outside the picture.